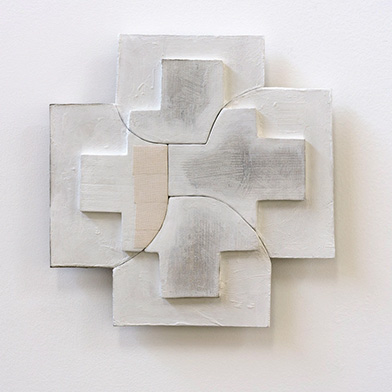

George Ohr’s radical shapes and modern glazes marked an important shift in three-dimensional vessel-making

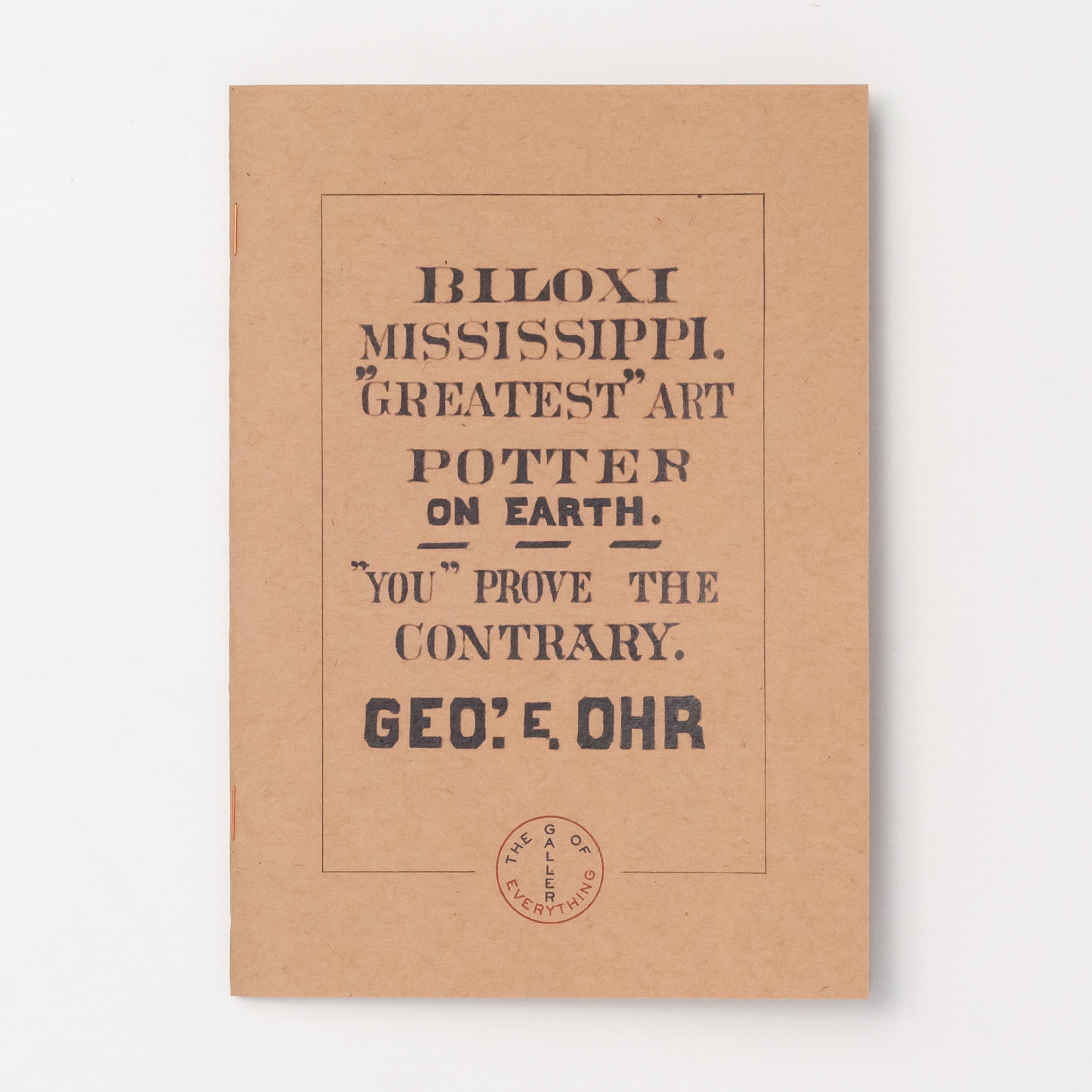

Just a few blocks from the shore in Biloxi, Mississippi a five-story wooden “pagoda” labelled “BILOXI ARTPOTTERY” towered above the train tracks that ran across Delauney Street. Approaching it, a visitor saw hand-lettered signs. One read: “Get a Biloxi Souvenir, Before the Potter Dies, or Gets a Reputation.” Another proclaimed: “Unequaled unrivaled—undisputed— GREATEST ARTPOTTERON THE EARTH.”

This eldest son of Alsatian immigrants developed an all-consuming practice and persona. Ohr’s clay pots were precise and prolific. Their radical shapes and modern glazes marked an important shift in three-dimensional vessel-making. As a body of work, they challenged not only the art establishment, but the cultural conventions of their day.

Yet Ohr’s proto-abstract experiments proved too unpalatable for local taste. Throughout his lifetime, the entrepreneurial mad potter of Biloxi was ignored and his legacy unrecorded in the history of American art.

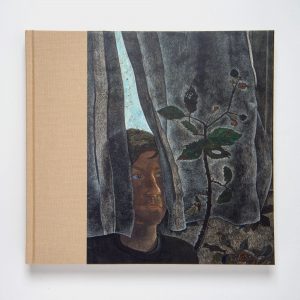

That changed seventy years later when the oeuvre was rediscovered by his descendants. Heralded as an unsung pioneer of modernist making, Ohr was soon being collected and championed by David Whitney, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. The latter was so enamored of the delicacy of Ohr’s material form, he repeatedly depicted the work in his paintings.

Reviews