In pursuing their idea of themselves in relation to the world, painters make everything subservient to them, transforming and transcending it. Standing in front of a blank canvas, they let their imagination run free, conjuring up their own world alongside the real world, coupled with the imaginary. Indeed, in each of their paintings, they allow us to experience the moment of creation ex nihilo, and each one raises the old metaphysical question anew: Why is there something rather than nothing? Between the painter and his or her pictorial imagination, there is no apparatus that would restrain their imagination. And through the brush with which they fill the emptiness of the canvas, they are more directly in touch with what moves them inwardly. In short, painters are freer than, say, photographers in their use of the visible.

Shara Hughes and Austin Eddy came up with the idea of exhibiting together not to be exposed to comparison, but rather out of a sense that, as different as their work is, there is a kinship between them. Painting as an evocation of an inner world. “It seemed logical,” says Eddy, “not only to exhibit together, but to do so in a specific way, reflecting not only the beginning and the middle of the artistic process, but also the cycle of life or the points of a relationship. The joint exhibition is both a tribute to our personal history and a potential for the future.” “For us,” adds Hughes, “it’s about our relationships and experiences in the world, how we relate to the political climate or to what is happening in our personal lives. Austin draws on still lifes, fruit, fish, or birds, and I draw on landscapes, whether that means focusing on a flower or a tree and using both as stand-ins for a figure. We both still deal with the same basic issues.”

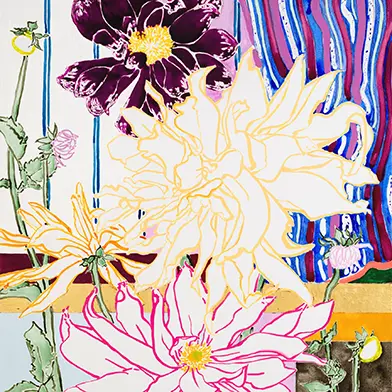

What do we see? In Hughes’s work, it is primarily trees, flowers, or the sun, but not in the way that nature dictates. The tree may have all its usual features—trunk, branches, and foliage—but, as in the peach tree in the painting Just Peachy (2024), these have been transformed into a red-green tangle of lines that create the illusion of both grass and leaves. The fact that she chose “a tree strewn with peaches” as her subject also has to do with her background, she says, “because I’m from Georgia, the American South. It’s a question of whether that connection comes to the fore or whether the image is completely abstracted from it.” By giving the impression of vital growth, Hughes’s depiction of the real goes beyond the mere repetition of natural beauty.

Speaking of abstraction, in Fruit Trees (2025) she departs from illusion and translates the concrete into the abstract. And she does it in a way that creates confusion about what we think we recognize. She alludes to red fruits, green-yellow grass, multicolored hills, and a yellow tree trunk with a crown whose green is punctuated by brown dots, and seamlessly blends them with the non-representational. The simplification of the motifs makes them difficult to identify. She pushes the mutual osmosis of the identifiable and the unidentifiable to the point where there is doubt as to whether the red shape really represents a fruit or a star, or neither. It is this process of abstraction that makes the landscape of ambiguous forms, patterns, and textures a mystery. Her use of color, both approaching and distancing herself from natural beauty, makes it clear that she is concerned with more than just the suggestive power of painting and making our eyes reel.

It is the tropisms that are triggered in her when she sees trees or fruit, and the jumble of inner moods that are projected onto the canvas through the movements of the brush. “I have the feeling,” she sums up, “that I’m always trying to paint a very simple picture where not much happens, but I can’t get away from myself. It always tends to be an organized chaos. It feels very much like me. When I see Austin’s work, I almost get jealous of how he can simplify everything. I think it also reflects our personalities.” Indeed, she tends to fill her paintings to the brim. It is as if she is driven to condense everything into a jungle of shapes and colors.

Austin Eddy, who also transforms figurative elements into abstract ones, takes a completely different approach. He also loves, as he says, “to be in nature, to internalize a landscape, but not out of a desire to depict what is right in front of me.” Like her, he is also “deeply interested in art history and the painters who came before us, and those who work alongside us. We both think more about composition, color, and painting than about the outcome of a painting of a fish or a peach tree.” Unlike Hughes, in whose paintings forms blur into one another, Eddy emphasizes their demarcation.

In Vulnerable (2025), the eye is drawn to a halved apple with a core in front of a green and black rectangle, with a bar containing a yellow dot on the left and a brown dot on the right. The inside of the red-rimmed fruit is white, the core is gray, the stem and leaves are green, and the seeds are black. The background, consisting of a white surface with a brown stripe, could be the wall of a room, but it doesn’t have to be. What seems to be namable, at the same time tips over into ambiguity due to the symbiotic coexistence of abstract, partly geometric forms, which clearly refer to realities, with a multitude of indefinable ones. What is certain is that the halved apple showing its core stands for vulnerability, for emotions whose source is autobiographical. “Basically, it is me who shows the viewer my vulnerability, which is lost when it becomes this apple. The apple is me,” says Eddy. All Great and Precious Things is the title of another, smiley-commented still life, with a banana, apple, and pear in the foreground and geometric, monochrome and green-and-white striped surfaces in the background. The arrangement of the fruits suggests that they function as metaphors for figures communicating with each other.

In essence, both Hughes and Eddy translate autobiographical material into abstract allegory, removed from their own lives. In general, trees and fruit are stand-ins for figures, which has the advantage that no information about gender, nationality, or age is needed. The principle of lack of identity applies to both. As well as the will to connect with the chaotic world through painting.

Heinz-Norbert Jocks

all images © the gallery and the artist(s)