Open: Mon-Fri 9.30am-5.15pm & by appointment

The Fuller Building, 41 E. 57th Street, 9th Floor, NY 10022, New York, United States

Open: Mon-Fri 9.30am-5.15pm & by appointment

Visit

See Verso: A Guide to Looking Back

Hirschl & Adler, New York

Thu 30 May 2024 to Wed 3 Jul 2024

The Fuller Building, 41 E. 57th Street, 9th Floor, NY 10022 See Verso: A Guide to Looking Back

Mon-Fri 9.30am-5.15pm & by appointment

Artists: David Ligare - Angela Fraleigh - Winold Reiss - Honoré Sharrer - Alan Feltus - Louisa Chase

History is the present. That’s why every generation writes it anew. But what most people think of as history is its end product, myth.

—E. L. Doctorow

“See Verso” is most often seen in the registration notes for a work of art. Labels, inscriptions, and dates find themselves grouped in with this term to describe the contents found on the backs of pictures. But what does see verso mean when taken out of this literal context? It is an indication that there is something more; you must look back to produce something new. See Verso: A Guide to Looking Back showcases an eclectic group of modern and contemporary artists who look back to their art predecessors as a means of fully understanding them.

Each work in See Verso possesses a unique mythic quality. Greco-Roman classicism, the art historical canon, biblical narratives, and the natural world are adapted onto canvas and paper as allegories, symbols, and as subjects themselves. Through these references, the artists are inviting us to look to history’s so-called “end product” to examine the present, and in turn render it changeable. Perhaps these myths shift or challenge perceptions. Perhaps they heighten them. One thing is for certain: they ensure that history is not left in the past.

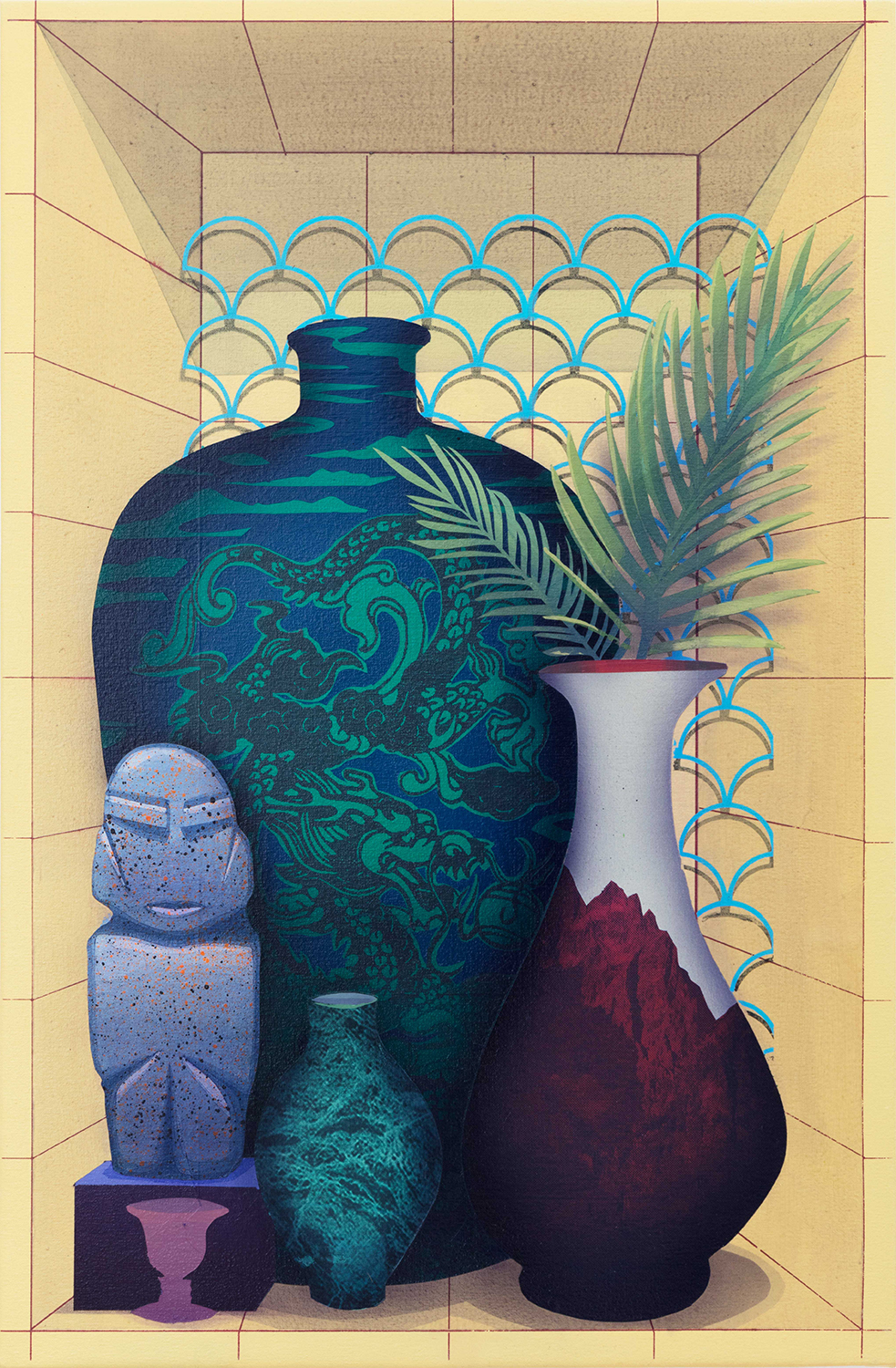

David Ligare looks back to Greco-Roman classicism, seeking a way to redirect contemporary culture away from a present moment defined by “intense popular distractions,” and “a strong disinterest in education.” He takes inspiration from ancient still-life traditions, depicting xenia—pictures of the foods given to houseguests—‚and rhopography—depictions of ordinary objects. His still life compositions are reverent, with altar-like settings, some even titled as “offerings.” Ligare sees the source of western art as a means by which we can reengage with the innate desire for knowledge.

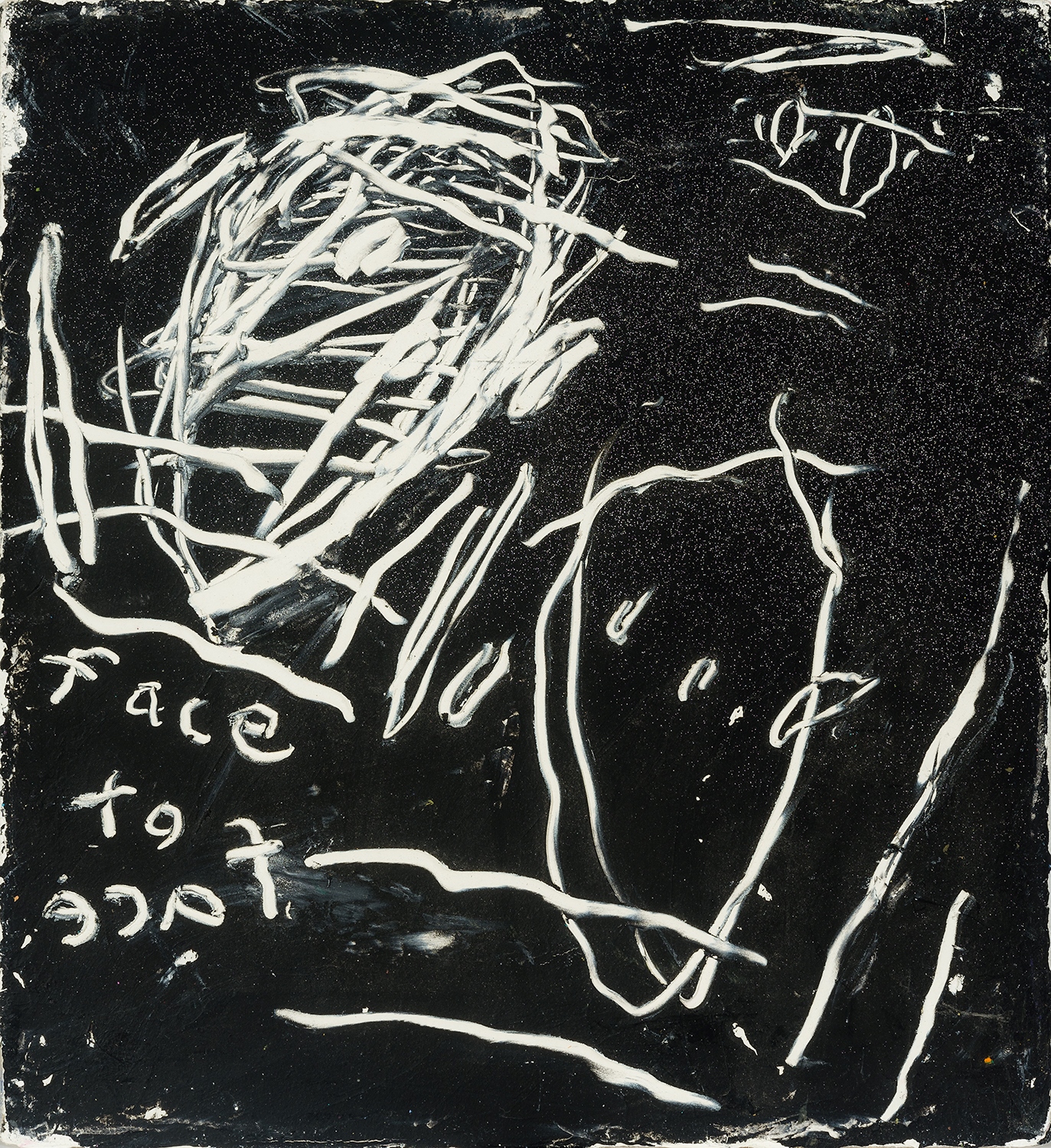

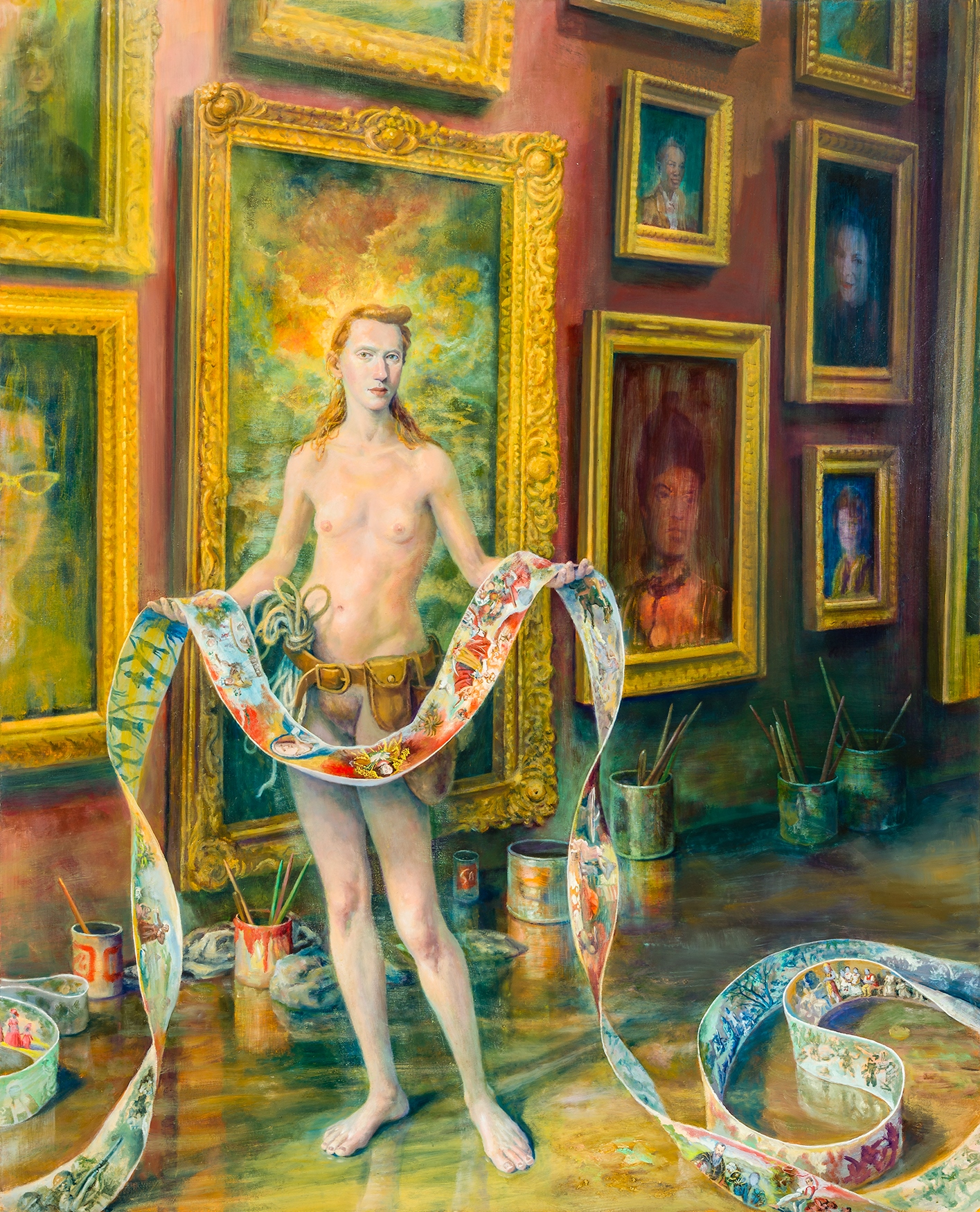

Angela Fraleigh similarly looks to classicism, but unlike Ligare, draws from the references employed by western artists throughout art history rather than addressing it at the source. Her portraits of classically rendered women are intimate, yet monumental. Her work seeks to upend the hierarchies long imposed upon women as subjects through contemporary representations and attitudes. In I Wake Knowing that I Will Sing Again, if I promise to never look back, Fraleigh directly references the Maenad in Emile Lévy’s Mort d'Orphée (1866) as a response to the overturning of Roe v. Wade and its implications on the bodily autonomy of women.

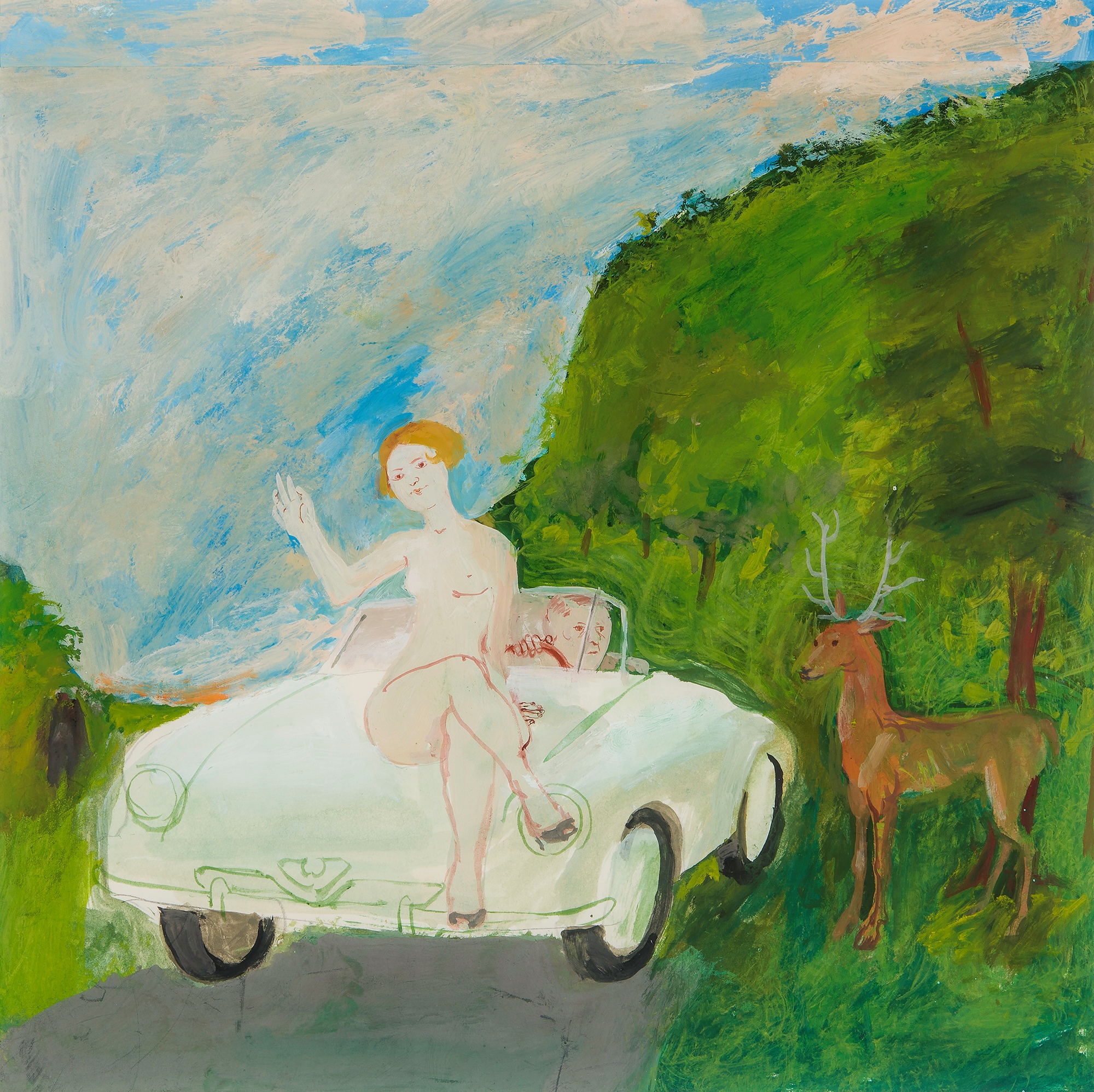

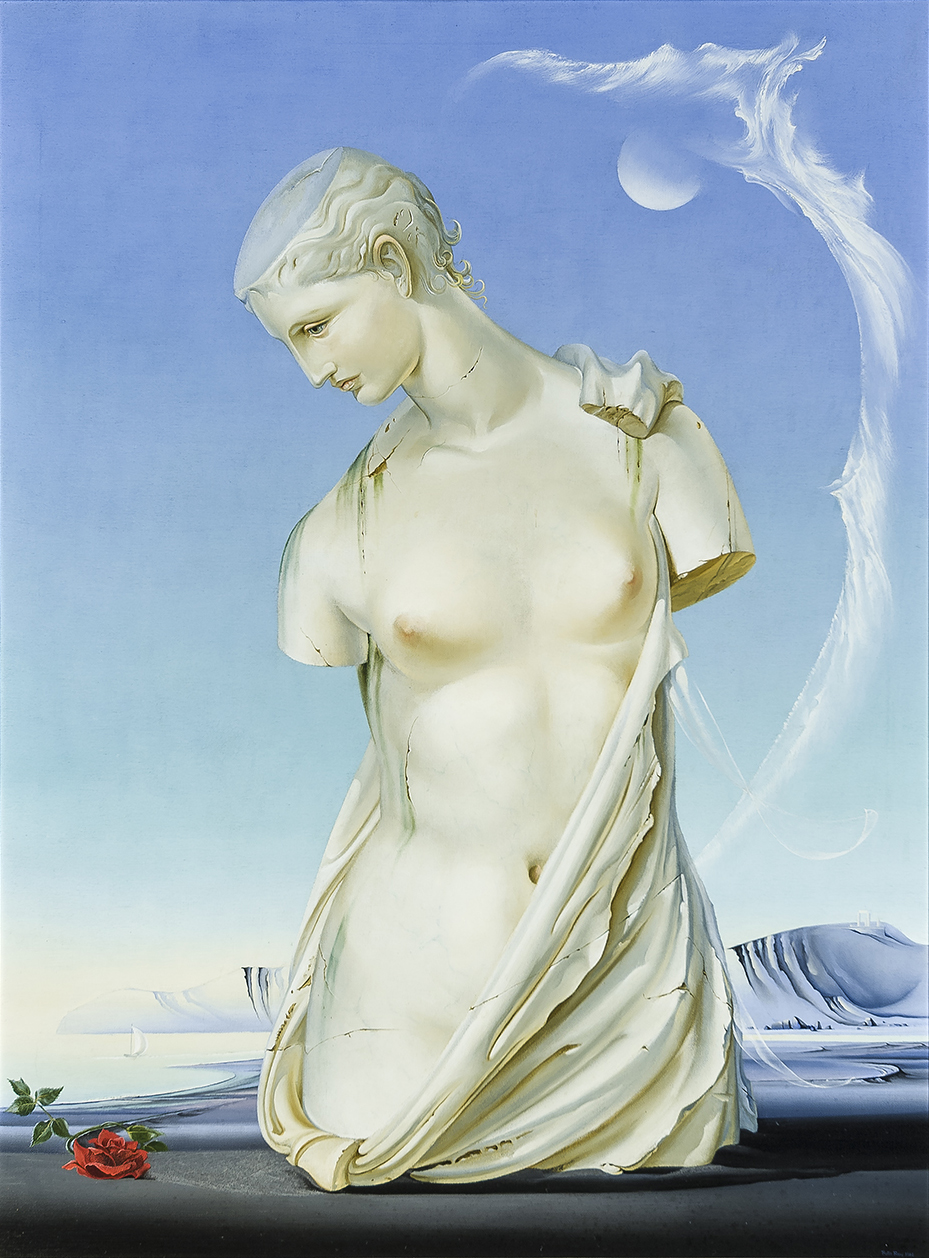

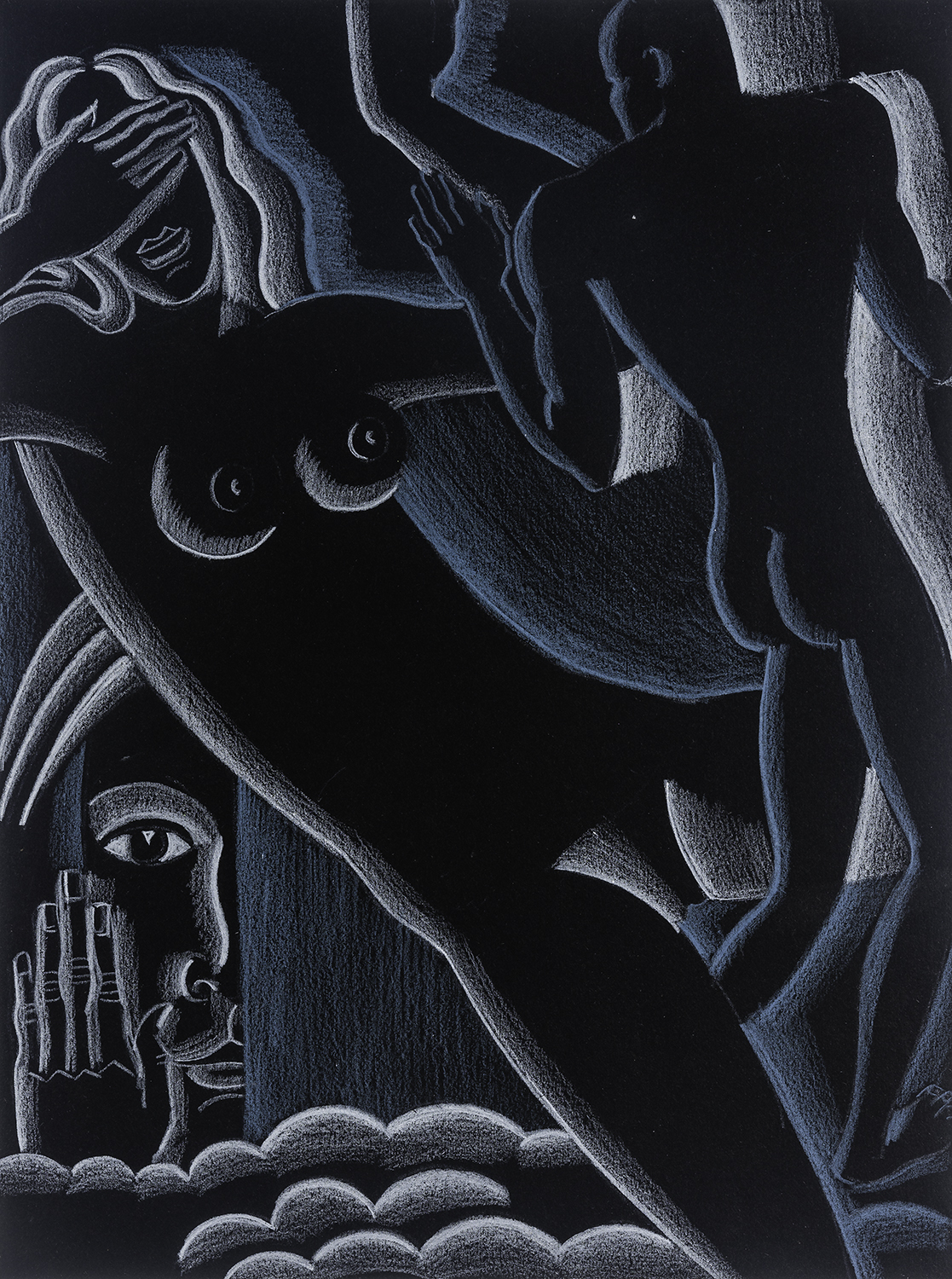

One can also find classical iconography in the magic realist paintings of Ruth Ray. It may be tempting to call her a surrealist, but Ray repudiated this label. She acknowledged the role that the subconscious played in her artistic practice but described it as being filtered through “the conscious—the rational mind” before translating it onto canvas. Her reimagined art historical subjects are now dreamlike visuals, thereby creating a new comprehensive vocabulary. Venus de Milo is titled after the famous ancient Greek statue of Aphrodite in the Louvre Museum in Paris and features a reimagining of the sculpture as a way of referencing the passage of time and the fleeting nature of beauty.

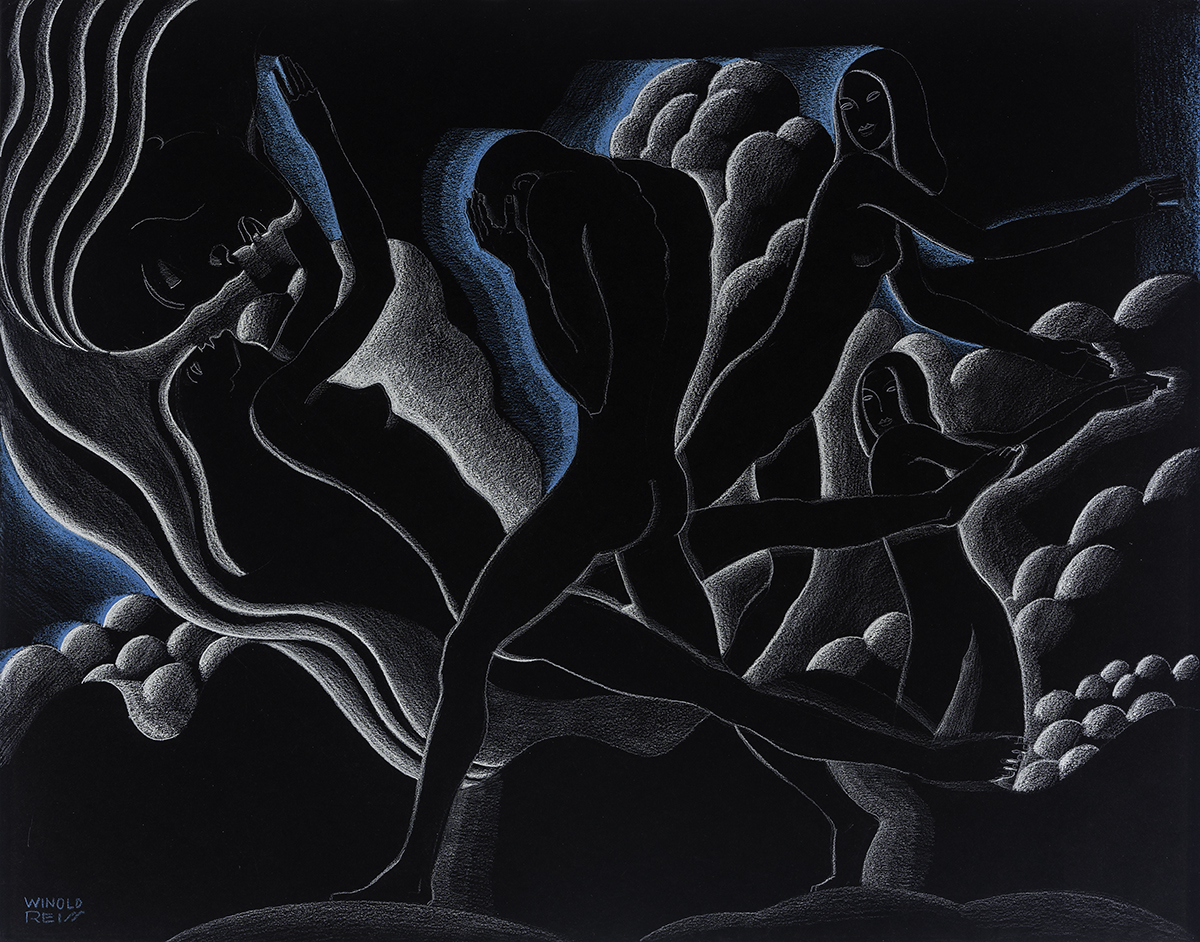

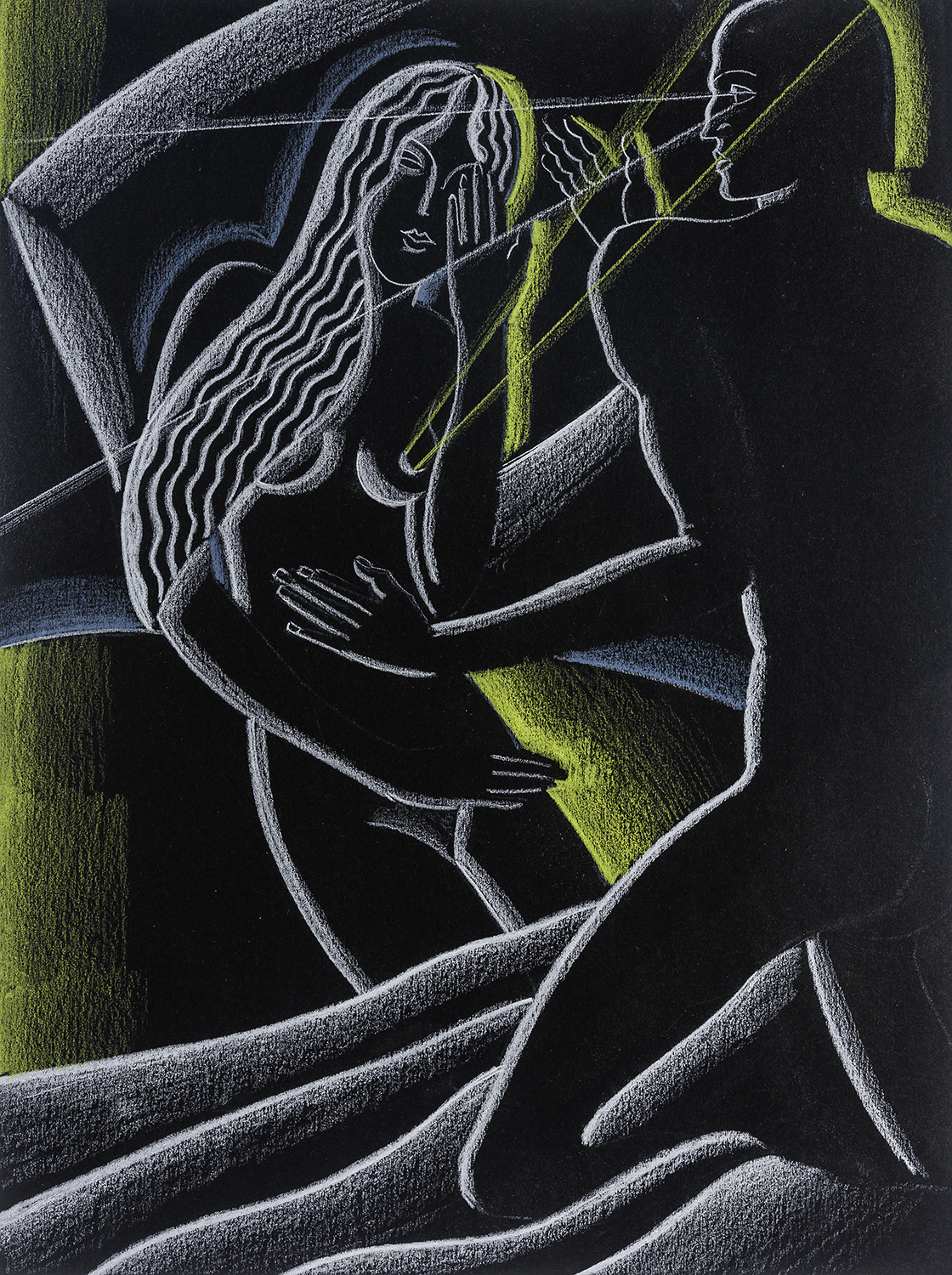

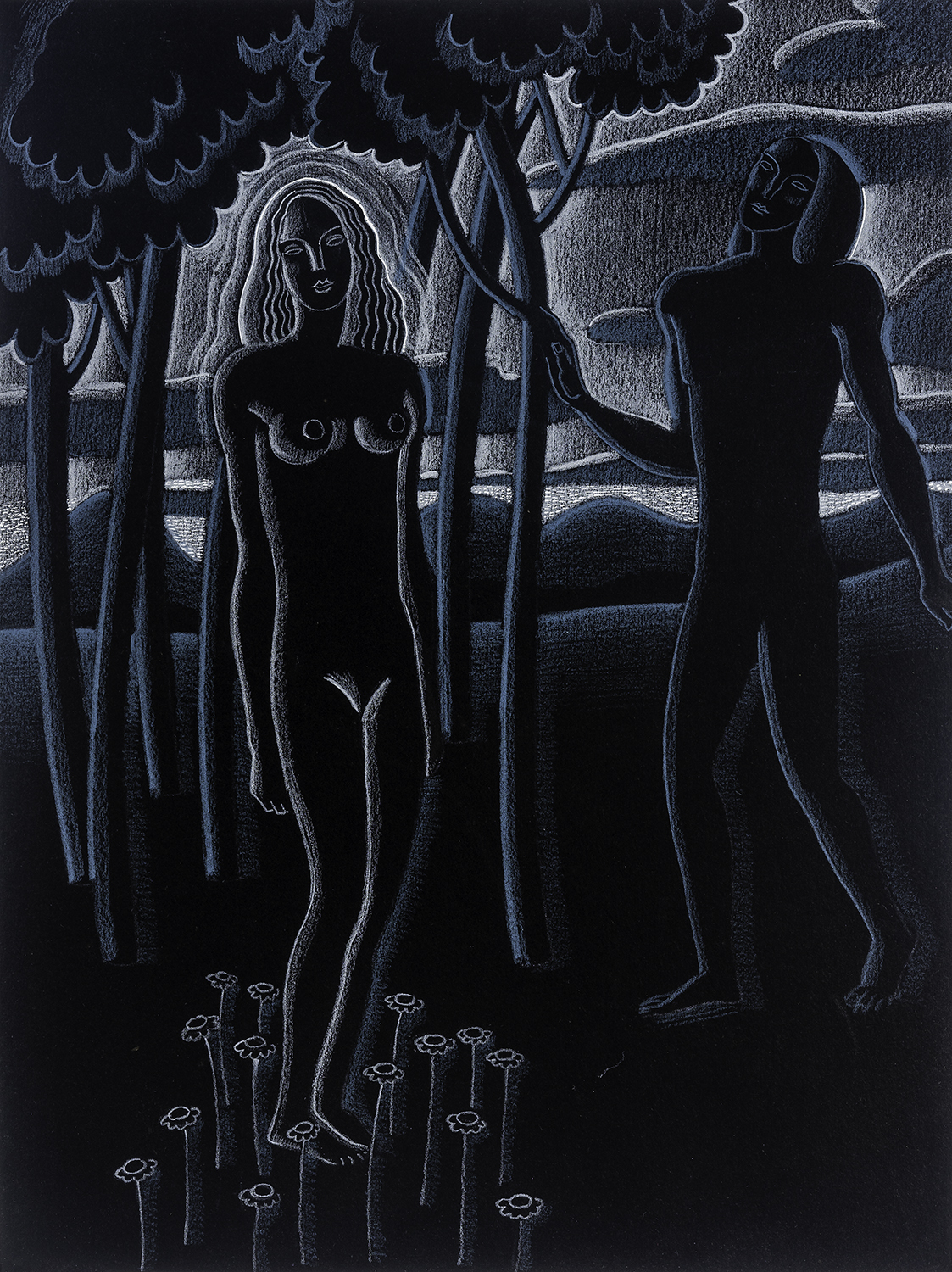

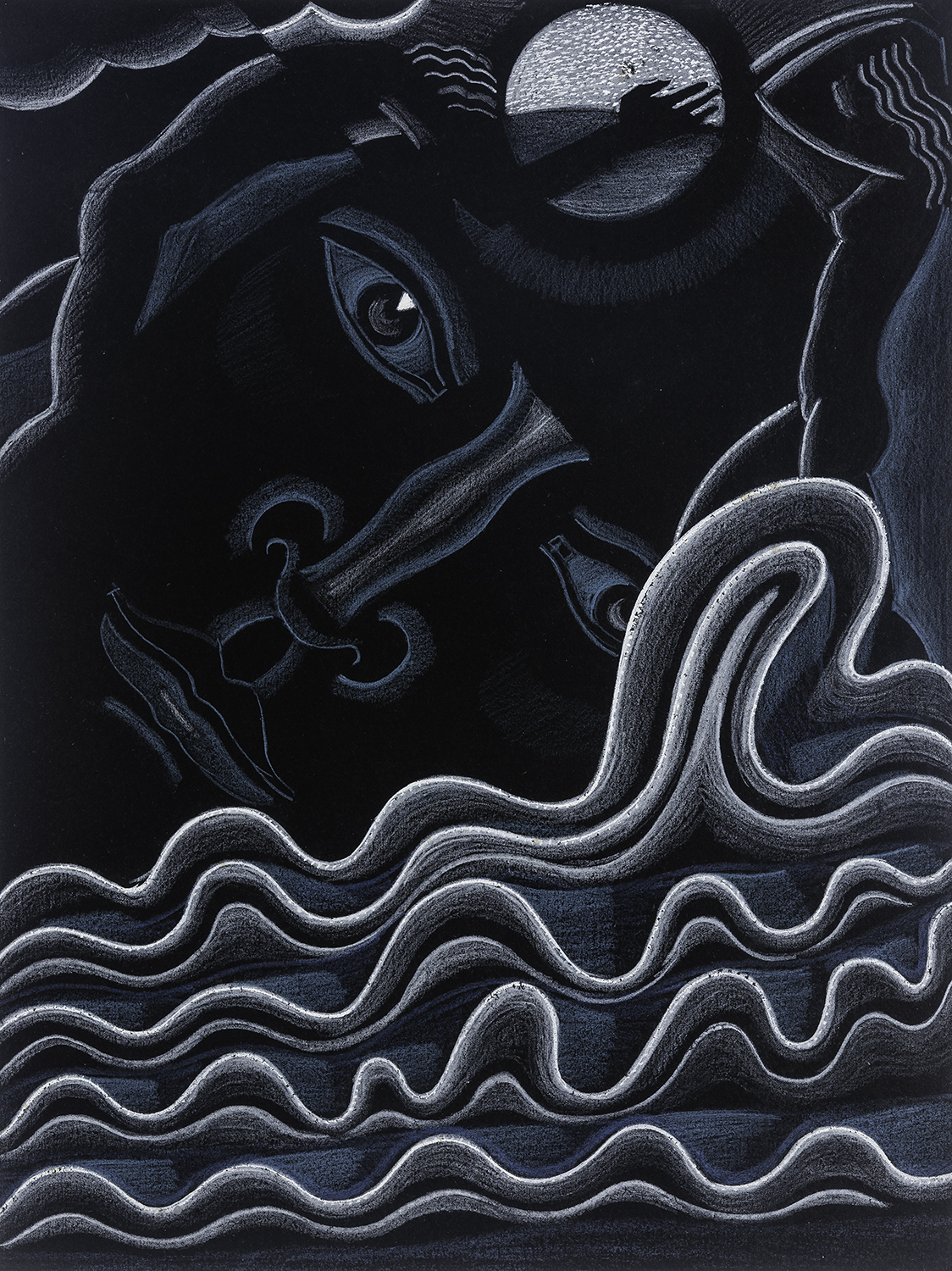

Winold Reiss instead turned to biblical sources to confront his contemporary experience, using the lens of John Milton’s “Paradise Lost” in a deeply personal manner. As part of an oeuvre that he produced without commercial intent, eight illustrative episodes of the epic biblical poem retell the story of Adam and Eve from the book of Genesis; ultimately, concluding with their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. It is likely that Reiss saw something of his own life in the story of the first two humans. He was a lifelong wanderer, an immigrant who was never entirely at home in his native Germany nor in his adopted home in the United States.