Open: Tue-Sat 11am-7pm

807, 8/F, K11 ATELIER Victoria Dockside, 18 Salisbury Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Open: Tue-Sat 11am-7pm

Visit

Emma Webster: Vapors

Perrotin Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Tue 25 Mar 2025 to Sat 17 May 2025

807, 8/F, K11 ATELIER Victoria Dockside, 18 Salisbury Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Emma Webster: Vapors

Tue-Sat 11am-7pm

Artist: Emma Webster

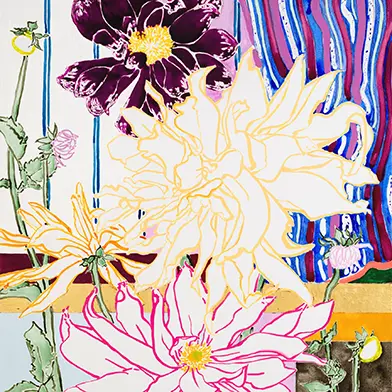

Perrotin presents Vapors, an exhibition of paintings by British-American artist Emma Webster, marking her solo debut in Hong Kong. The 11 canvases, painted during the Los Angeles fires this January, show ethereal, empty landscapes imbued with an unsettling, atmospheric calm. Some paintings suggest the arrival of unfathomable calamity, while others impart the cool surrender of catastrophic aftermath. In these works, Webster invents a wholly new genre of painting that blurs the boundaries between plein-air landscape, still-life, and virtual reality.

Last year, California—where the artist currently works and resides— experienced a record-breaking dry season, which ultimately contributed to the recent wildfire in LA, wiping out entire ecosystems and neighborhoods. The world watched online as Pacific Palisades, the neighborhood where Webster’s maternal family is from, burned to the ground. Despite the urgency to reverse climate change, efforts remain focused on mitigating symptoms instead of resolving the causes. This tragic complacency and surrender to illusion seep into Vapors.

For Webster, the state of the climate is existential. Working during the devastating wildfires near her studio, she was reminded of the nightmarish global pandemic—wearing masks, doom-scrolling the news, on the prowl for air purifiers, learning of losses from friends and family. All of it exacerbated by an antithetical bewilderment: What can be done? Reflecting on the experience, Webster describes the uncomfortable banality of daily life, stalled and suspended, despite the terrible and profound disaster outside. This sense of lost gravity is apparent in every painting.

Vapor, a natural ghostly phenomenon of suspended liquid in the air, is often a fleeting result of change: temperature, atmosphere, weather, and environment. Moreover, vapor is barely perceptible to the human eye and is most often associated with breath. It is the moment when our inner and outer worlds collide. “To have the vapors” connotes melancholic humor—it was a term to describe feeling depressed or emotionally “under the weather.” Vapor’s ethereal, transient, and transformative qualities, both in nature and metaphorical dimensions, ring in the paintings’ misty greys and thin glazed brushstrokes.

Much like the lineage of landscape painting itself, Emma Webster does not reproduce vistas from real life, but cobbles together worlds to paint from. Landscape in the sixteenth century was first conceived as background and then came to signify scenery. Depictions of nature were conceived from a purely human vantage point as a stage set for human actions, perceptions, and material exploitations. As the industrial revolution inspired a pastoral exodus, man set to carving the landscape to suit his whims. Human agency transformed nature in ways that would come to threaten it; the effects of which we are forced to contend with now.

Webster first adopted sculpture studies as means of creating spatial realism in her paintings. This germination began when she briefly worked in set design before furthering her studies at Yale Graduate School. Her hybrid creative process involves making sculptures both in and outside of the computer. She crafts objects with wax and plaster, then 3D-scans them, and integrates them into her digital dioramas. Using the computer, she combines VR elements with sophisticated light rendering, which she then projects and paints onto canvas. Webster’s workflow is porous. As these virtual and physical worlds change hands, boundaries are reimagined, and spectators are encouraged to question what is real and what is fantasy.

Using digital prosthetics such as the Oculus and Blender, Webster is among the first artists of her generation to repurpose these tools for painting. From orchestrating gestural sweeps to painstakingly fine-tuning minute details, her pictures lull the spectator with their phantasmagoric and painterly delight.

In these paintings of no man’s land, birds—whose instinct is to fly—are portrayed in static postures, implying their unnatural, even dire circumstances. In Alaska, a calcified vulture is perched and stiff; the Sparrow is pinned in mid-air; Odette, an abstracted swan, part-drawing part-frame sits under a dolmen; even the bulky Black Bird with a Mooresque musculature is weighted, planted in a desolate vista. What these paintings have in common is also the dominating physical presence of the singular animal, occupying a large portion of the image, bringing to mind portraiture in the Romantic era. Meanwhile, their mythical personas are suggested by the visual features of taffy surfaces and the eerie dimensionality of 3D rendering.

Unlike most of Webster's terrains and vegetation, which are “grown” digitally using the Oculus, the shrubs in Brushwood are adapted from 3D scans of a bonsai tree. Already an artificial form of nature that has been manipulated and controlled, the bonsai scan amplifies its digital glitches, further heightening its falsities. Additionally, its scale inversion transforms it from miniature to giant. The tree is illuminated by a dramatic radiance, similar to the golden beams around the sacrificial lamb in Jan van Eyck's Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. Its swept, tendril branches sway in invisible tumult. The winds of change are not always placid.

Evolving from the sci-fi terrains of Illuminarium, her first show with Perrotin, Webster here opts for stark, refined compositions, where vastness is hard not to conflate with loneliness. Woodside, named after the street of her childhood home, also literally means the wood left on the side. In both interpretations, the forest is “placed.” The sun is painted between the trees and their shadows, using techniques similar to sfumato, pioneered by greats such as Claude Lorraine and Nicolas Poussin. Contradicting light sources create unusual, improbable scenes where the long-cast shadows are oddly illuminated.

The Means That Make, portraying a solemn clover with an expansive sail above, introduces a new spiritual discourse in her work. Like the visionary spiritualist painters William Blake, Frederic Church, and Agnes Pelton, Webster uses light to speak to the spirit. The luminous crack of the horizon resembles a seam splitting open into the beyond. Within it, we find an omnipresent breath, equal parts invocation and revelation.

Emma Webster’s practice mirrors the soul-searching of our zeitgeist, in which we must contend with both our environmental impact and AI sentience. The ground shifts beneath us; the bonsai becomes behemoth; the mountain, molehill. The winds change course. We inhale, we exhale. We call out, the vapor of our breath our only trace.

Edited based on text by Fiona He Xiao