by Astrid Bernadotte

Internationally celebrated for his humorous and playfully ambiguous sculptures, Franz West revolutionised the concept of sculpture through his pioneering efforts that explored the relationship between art and the viewer. His oeuvre spans a number of different media that include painting, collage, furniture and installation. West was heavily influenced by various performance art movements of the 1960s, including the Viennese Actionists, which he interpreted into an interactive series of papier-mâché sculptures known as Adaptives or Paßstücke. With this breakout body of work, West redefined the spectator’s experience with sculpture by creating an active dialogue between the two. Believing that art should have a function, West’s sculptures are both physically and intellectually immersive for the viewer, and it is through his experimental and innovative use of form, materials, language and colour that West set a new precedent for sculpture from the second half of the twentieth century.

EARLY LIFE

Franz West was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1947. His father was a coal trader and his mother a dentist, whose practice was adjacent to the family apartment in a modern public housing project named Karl-Marx Hof. West recalled a very regimented childhood following the Second World War and recounted a ‘time of darkness’. His playground was amongst the ruins of the War, nestled within the burnt rubble and shattered glass of bombed houses in his neighbourhood.

VIENNESE ACTIONISTS

As an adolescent, West grew up in a politically conflicted time. Post-War Vienna was struggling to extricate itself from its recent troublesome history. Many people during the War had either joined or were forced to join the Nazi Party, and the majority of the Viennese shied away from confronting their past. This reticence spurred a number of political and artistic counter movements in the 1960s, one of which were the Viennese Actionists, who were part of a short-lived yet influential movement of controversial performance artists that directly addressed the horrors of the war and Austria’s role within it. Their aim was to shock the public out of their conservative traditions with outrageous public acts of sado-masochism; West was profoundly affected by the violent and provocative outbursts of the movement. He was present during an infamous performance in 1968 by Günter Brus, a co-founder of the group, who masturbated in public whilst simultaneously smearing his body with his own faeces and singing the Austrian national anthem. Brus subsequently served a six-month prison sentence for ‘degrading symbols of the state’. West also witnessed Hermann Nitsch, another founder of the movement, disembowel the carcass of a dead lamb on top of a white canvas, which caused weeks of distress for the teenager.

West rejected the aggressive ideologies of the Actionist movement, opposing their macabre seriousness and instead sought to incorporate humour, wit and philosophy into his art. He did, however, draw upon and modify a number of the Actionist’s principle foundations, such as the notion that the human body can be used as a living canvas, as well as their innovative use of ordinary household objects in their performances. Incorporating objects such as buckets, musical instruments and empty bottles, they re-contextualised their function by removing them from their associated setting and instead placing them in bizarre and challenging environments. Additionally, West and the Viennese Actionists shared the belief that art can be used as a tool to access the human psyche, albeit through very different methods; West steered clear of the shock factor, instead preferring to subtly engage the subconscious through his work. The Actionists provided West with the provocative tools that would help to lay the foundations of his work.

During this period, West constructed witty collages using popular newspaper advertisements and a bricolage of cut-outs from soft-porn magazines. He fused seemingly random text and images together to create comical conclusions that, at times, directly poked fun at the Actionists. From the very beginning of his career, West playfully manipulated everyday imagery and materials in a novel format.

A MOTHER’S INFLUENCE

Throughout his youth, West struggled with a sense of displacement. His mother was Jewish, but his father was not, which meant that his family were not fully accepted into either of their local communities. For a certain period, West became part of the first wave of the Beat Generation; a literary movement whose work would later greatly influence American culture and politics. In line with the lifestyle of the movement, he experimented with narcotics, travelled aimlessly to Baghdad and Tehran, and caroused about in cafés in Vienna with other Existentialists. It wasn’t until 1977, at the age of 30, that West enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, where he studied under Bruno Gironcoli.

It was largely to appease his mother that West finally decided to pro-actively pursue a career in art. She was exasperated with his idleness and believed in his artistic potential. As a child she had frequently travelled with West to other European countries to admire the classical architecture of churches and to study Renaissance paintings. As a result, West greatly credited his mother as a source of both motivation and inspiration. He humorously cited that his first interaction with Actionism was through his mother’s dental practice. After the War, anaesthetic in Vienna was scarce and West recalled the screams that would emanate from his mother’s surgery. She would later emerge in the doorway with her apron covered in blood. West jokingly believed she was subconsciously an Actionist or at least deserved to be an honorary member. His mother also sourced his first experimental material of white gauze and plaster from her surgery.

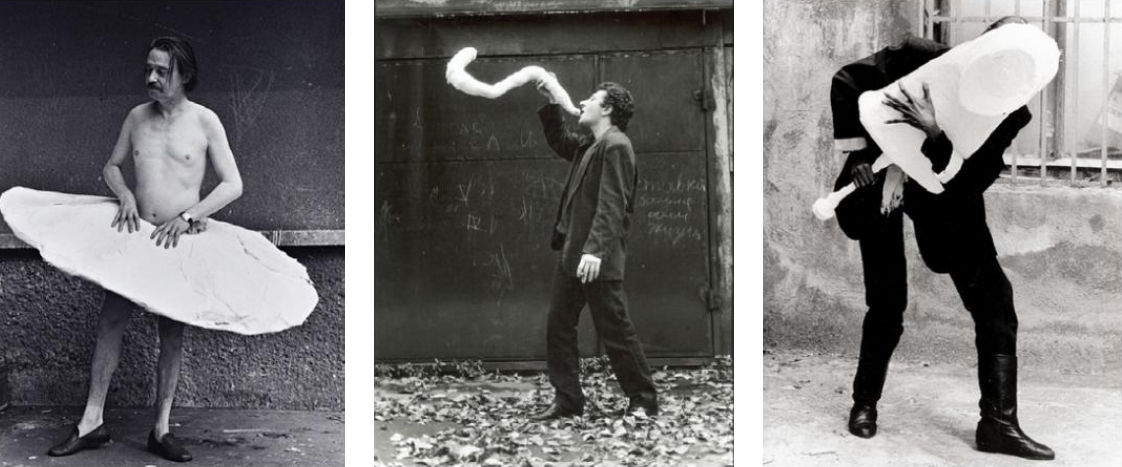

ADAPTIVES - PAßSTÜCKE

Experimenting with everyday materials led West to discover the bountiful qualities of papier-mâché; a medium that today has become synonymous with his practice. The material was used to create one of his most famous body of works, the Adaptives, also referred to as Paßstücke. The name was coined by the Austrian poet and West’s great friend, Reinhard Priessnitz, and fittingly describes their purpose - to adapt to the human body. These early sculptures were first constructed in the mid 1970s and by using papier-mâché, wire, plaster or polyester, West could easily sculpt ambiguous organic forms that would later harden to become rock solid. He typically painted them white, as he believed colour would distract from their arbitrary functions. Light-weight and only a few feet in size, these portable sculptures are interactive, demanding the viewer’s intervention rather than observation. West famously stated that “it doesn’t matter what art looks like but how it’s used” and argued that there is beauty in function. Modernists such as Le Courbusier, championed the notion that if something is of high quality it will work perfectly, and it is within that perfection that beauty arises and as a result ‘form follows function’. Similarly, West’s aesthetics derive from not only their visual quirkiness but also from their use. The participation of the viewer is paramount and only by holding, touching, wearing or using the artwork in some way are the Adaptives deemed complete.

West was a great admirer of Joseph Beuy’s, who once told him that “every human being is an artist.” West took this concept literally and incorporated this notion into his work. The artist and the viewer equally collaborate to shape the artwork’s meaning; the artist by creating the work and the viewer by reacting with and interpreting the sculpture. Adaptives are also referred to as prosthetics, which reflects one of their many functions: to be an extension of the viewer who is an integral part of the process.

Franz West, Untitled (Hat), 1983.

West challenged traditional concepts of sculpture and eradicated the taboo of touching art. He demolished hierarchy in the relationship between the viewer and the artwork by inviting physical interaction. The concept of picking up a work of art is counter-intuitive to most, but through these radically immersive Adaptives the constraints of the “normal” art experience is liberated, and an ongoing dialogue is formed. Art was no longer passive and unresponsive to the viewer, one now had to address the work and think how to engage with it. Consequently, West earned the title of the ‘gentle anarchist.’

West was continually fascinated by people’s reactions to art and studied how others would conduct themselves in public and around artworks. Subsequently, West’s sculptures tap into one’s playful and inquisitive side, turning even the most serious of participants into comical performers. His work is purposefully captivating and designed to distract from the reality and troubles of daily life. They encourage the viewer to break out of their comfort zone and indulge in the innocence of slap-stick fun.

As the viewer physically interacts with an Adaptive, a performance is inadvertently created, one which parallels the Happenings and performance art movements that were prevalent during the 1960s and 1970s. The material itself relates to the theatre, as traditionally papier-mâché was used to create stage backdrops and masks. This connection is no coincidence and alludes to the many ways in which West would insert multiple hidden layers behind his seemingly simple and humorous sculptures. His work is simultaneously light-hearted and deeply philosophical. In many of his sculptures he incorporated everyday objects, items such as empty bottles, mechanical parts, legs of furniture, tinned cans or walking sticks. West transformed the mundane and ordinary into unfamiliar yet recognisable shapes. In reference to his sculptures he once claimed that he believed, “if one could see neurosis, this is what it would look like.” West’s innovative use of re-attribution distorts the status quo and disturbs the objects ability to fulfil its original purpose; one can no longer drink from the bottle or eat from the can. This change in function, challenges the viewers’ accepted norms of reality, where everything is neatly de ned, identifiable and easily placed, which in turn explores the psychology of how art is interpreted. Perhaps it is not surprising that psychology is at the crux of West’s work, considering that, through Freud, Austria is the birthplace of psychoanalysis. Freud had a heavy influence on West, so much so that he modelled his renowned divans on Freud’s therapy couch.

“The perception of art takes place through the pressure points that develop when you lie on it”

- Franz West

Franz West, Auditorium, 1992. Installation at Documenta IX, Kassel.

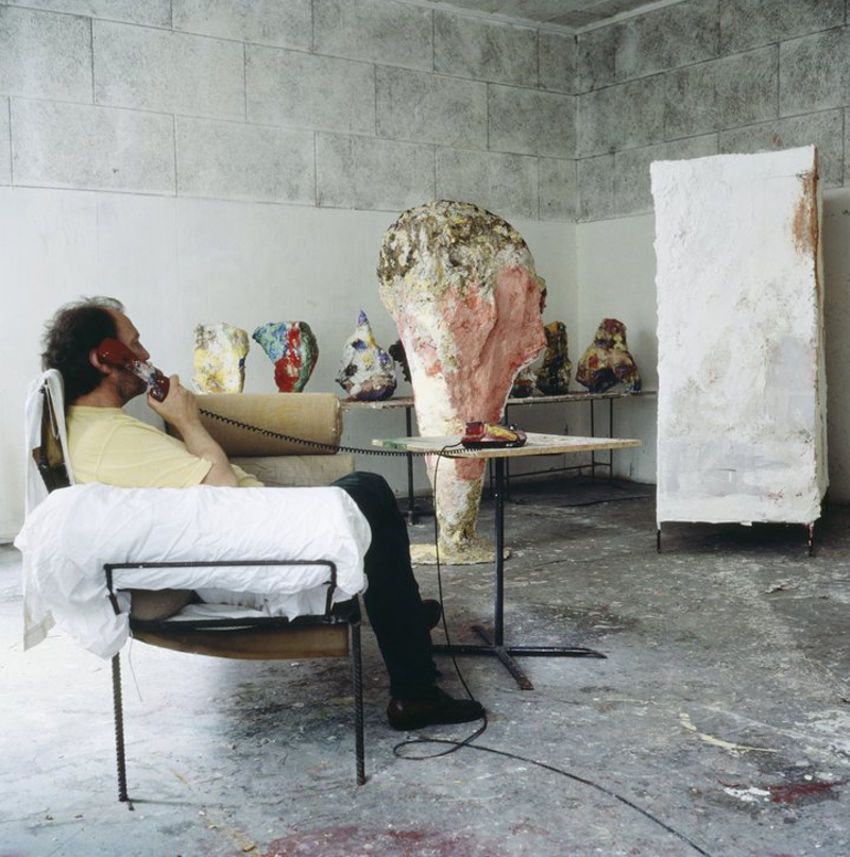

FURNITURE

In the early 1980s, West turned his attention to furniture. He fashioned divans out of metal, foam and wire, that were surprisingly comfortable, and referred to them as “Adaptives for the human body at rest.” During this period, West’s international reputation was growing, but it wasn’t until 1992 whilst exhibiting at Documenta IX in Kassel that he firmly placed himself on the art map with his conceptual and public installation - Auditorium. Made up of seventy-two upholstered divans covered in Persian rugs, the work was installed in an open-air car park. They were directly inspired by the famous divan in Freud’s office on which his patients lay during his psychoanalytical therapy sessions. Freud believed that the divan was an instrumental tool in relaxing the human psyche and West believed the same. His interactive installation took on a life of its own and it unintentionally became the meeting hub for visitors at the exhibition.

Auditorium exceeded its purpose of facilitating public interaction, both with his installation as well as with one another. Many of West’s works can be seen as functional social experiments; observational tools in decoding man’s relationship with art. This installation relied on man’s natural tendency to congregate, socialise and communicate. It functioned by opening up a dialogue with the human psyche, something which is at the heart of all of Franz West’s work.

“It doesn’t matter what art looks like but how it’s used.”

- Franz West

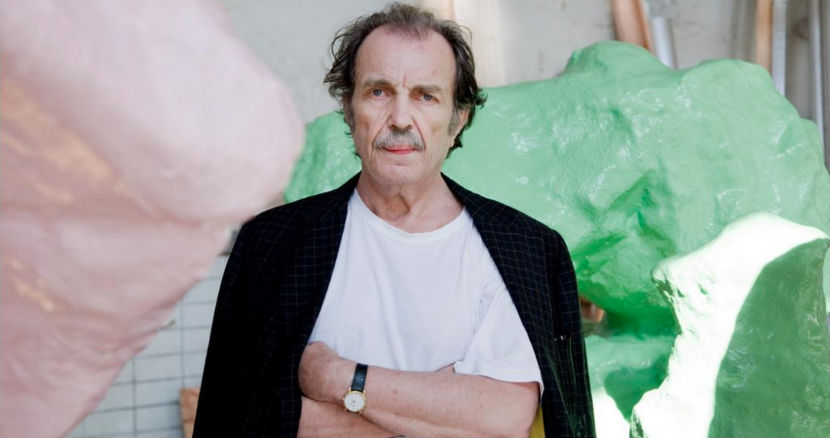

Franz West in his Studio.

LEGITIMATE SCULPTURES

During the latter part of 1980s, West’s artistic vision, which necessitated interaction between sculpture and audience, was at odds with the desires of commercial galleries, who preferred the works to remain untouched and to be displayed traditionally in order to maintain their financial value. West decided that if his pieces could not be exhibited in the way that he intended, he too would adapt. In 1986 at Neue Galerie in Graz, he debuted a new series of works in an exhibition with the self-mocking title, Legitimate Sculptures. These vague bulbous forms were created from papier-mâché mixed with polystyrene, cardboard and lacquer. Larger in scale they sat perched on top of handmade plinths that accompanied the works. They were no longer easy to carry and too fragile to handle. In contrast to the stark white Adaptives, these works were mottled in brightly coloured reds, greens, pinks and blues, applied in thick layers that defied gravity by dripping in all directions.

West strived for a more critical analysis of his sculptures from the spectator. He recanted on his previous invitation to touch the works, this time visitors were requested to interact intellectually instead of physically. These sculptures reached their completion through the viewers examination and through the various chains of associations that are triggered whilst engaging with the work. The sculptures’ arbitrary forms are immediately intriguing, as their bulky contours coax the viewer to investigate further and, in-so-doing, anthropomorphic qualities may often start to manifest. Upon close inspection, one can make out a nose, an ear, or a chin, but as soon as one grasps the physiognomy they vanish like a mirage, and the whole work morphs into something else entirely, such as a meteorite or an ice-cream cone.

OUTDOOR SCULPTURE

In 1990, West was chosen to represent Austria at the Venice Biennale, and years later, in 2011 he was awarded the Biennale’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. The 1990s was a period where he flourished, and West continued to push the boundaries of sculpture by exploring new forms and materials. He encountered the robust and glossy surface of aluminium, which was in stark contrast to the fragility and rough texture of papier-mâché. This new material allowed West to produce much larger and sturdier sculptures that could be placed outdoors. Never without humour and always venerating the mundane, West claimed his new oblong shapes, were inspired by the Viennese sausage. Although deemed to be abstract forms, their phallic shapes are purposefully suggestive and playful. At the same time, they act as satirical critiques of the soft porn industry, which West also touched upon in his collages.

Patchworked and welded together, these brightly coloured aluminium sculptures tower in public settings such as parks and town squares, naturally inviting passers-by to interact. Ambiguous from afar, their function comes into focus as one gets closer, as they provide a seat to sit on. Seating areas are often revealed by a protruding arm or a specific curve in the work. This concept echoes West’s memories from his trips with his mother; he evoked the benches he found hidden in church alcoves where one could sit and piously reflect. He wanted his art to also provide an environment where one could rest in contemplation.

Painted in hot monochromatic colours, sourced from a Toys “R” Us catalogue, bubble gum pink, baby blue, forest green and submarine yellow, the colour palette adds to the toy-like quality and playfulness of the sculptures. Although, West did not view himself as a great colourist, colour is a key element in his work. The bright white of the Adaptives call to mind a blank canvas with endless possibilities, as well as a sense of purity and innocence. In his later works, the vibrant colours act as a honey trap that draws the spectator in and, like a magpie, one is enticed to touch the glossy surface. The use of pink features heavily, either as a bold blanket of colour or sprayed on top of other layers of colour and is a reference to his mother and her dentistry; pink being the colour of dentures and gums.

These sculptures come in various forms, sometimes worm-like or as twirling ribbons or spheres. As a result of their obscure shapes and bold colours, they are devoid of any responsibility to fit in or adapt to their environment. West wanted to offend nature in order to create a dialogue, therefore the more garish the colour the more sublime the work became to him.

Both intrusive and inviting, these sculptures create their own environment where form and function are roughly compatible rather than mutually exclusive. West stated that he never planned his works but instead, like the Abstract Expressionists, believed that spontaneity was key in finding complex order in disorder.

Franz West, Untitled (painted by Herbert Brandl), 1986.

COLLABORATIONS

Throughout his career, West collaborated with a multitude of artists, often inviting them to paint his papier-mâché sculptures as well as make additions to his collages. He would also frequently include works by other artists into his own exhibitions. West never believed in the notion of the individual artistic genius, nor the creation of a great masterpiece. Instead, he was interested in collaborations. In the same way that he invited the viewer to complete his works through interacting with them, West invited other artists to paint his papier-mâché creations. Throughout his career, he worked with leading visual artists, including Douglas Gordon, Marina Faust, Mike Kelley, Sarah Lucas, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Rudolf Stingel and Herbert Brandl. From 1988, an intense collaboration between Brandl and West had developed. Brandl frequently painted West’s sculptures and participated in the creation of his works, but they also collaborated on involving the viewer in both of their works simultaneously. In 1994, for an exhibition at the Lisson Gallery in London, suitably titled Konversation, Brandl produced a painting that depicted an eye that was to be observed whilst drinking wine from a vessel that West had created.

For West, collaborations were not only important to expand and finish his works, they also helped to illustrate and solidify the concept that producing art is an open and interactive process.

Installation view of Sisyphos Sculptures, 2002 at Gagosian Gallery, London, 2018.

SEMANTICS

The importance of colour, form and function is visually evident in West’s work, but equally important is his subtle use of language to provide multiple contexts for his arbitrary forms. West was strongly influenced by renowned philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who explored the various tools of language and semantic games. Wittgenstein argued that the meaning of a word is its function, but this meaning is not necessarily exclusive to referencing one thing; words are not fixed, but instead are dependent upon their context. West applied this theory to his art, allowing art to have meaning through multiple interpretations. Subsequently, West preferred to use the word ‘object’ instead of ‘sculpture’, in reference to his own work. He argued that ‘object’ is a word associated with an abstract form whereas ‘sculpture’ denotes figuration.

Although West insisted his work not be limited by a set meaning or single construct, he often used accompanying text to suggest a particular conceptual aspect of a piece. His 2002 series entitled Sisyphos is indicative of his use of philosophical archetypes that simultaneously reference classical mythology. These painted mounds of papier-mâché, cardboard and Styrofoam are named after the mythical king Sisyphos, who was punished by Zeus for being devious and conceited. He was sentenced to eternally push a heavy boulder up a steep hill, only for it to roll back down as soon as he got within reach of the top. The title of this series alludes to the eternal struggles and frustrations that artists are doomed to endure in their artistic pursuits. However, without its title, it would have remained completely abstract and without context. West continued to make similar works which resembled large heavy boulders throughout his career but gave them different titles or none at all.

West also provides nonsensical titles to provoke viewers; such was the case with his 2013 retrospective at The Hepworth Wakefield Museum where he played with free association. West sadly died in 2012 during the preparations for the exhibition but on his death bed, when asked what he wanted the show to be called, he replied “Where is my Eight?” West was satirical to the very end, as none of the curators understood the meaning behind the title. For the last time, he demonstrated that ambiguity opens an infinite number of interpretations, which then create personal dialogues with the viewers.

From the very beginning and in contrast to his peers, Franz West declared his allegiance to sculpture and was committed to the importance of physically creating a work of art. For West, without a physical entity, the ability to engage the viewer and form a dialogue would be lost. This exchange between viewer and artwork is paramount, be-it through touch or interpretation, dialogue lies at the foundation of Franz West’s practice. His innovative use of materials, form, colour and language, blurred the lines between sculpture, installation and furniture. As a result, West created new archetypes for sculpture that allowed the viewer to intervene and interact. His sculptures captivate us because, although they are inherently ambivalent, they provide small glimpses of recognisable shapes, hidden in the contours of the work. He taunts our instant re ex to identify and contextualise what is in front of us, highlighting the psychological need to understand and dispel the abstract. This, in turn, plays an important role in opening the human psyche, as every person’s experiences are individual.

Franz West, Untitled, 2007.

There is no single concept or prescribed meaning that West conveys. He used abstract forms to create a multitude of different interpretations which can alter from day to day, depending on the individual and their state of mind. West’s sculptures demand attention, drawing the viewer into a world that is both ambiguous and unnerving at times. They are simultaneously philosophical and literal, and it is through these revolutionary constructs that he has altered our perception of sculpture forever.

Astrid Bernadotte is Gallery Director at Omer Tiroche Gallery, London.

Franz West: Indoor Sculptures is on view at Omer Tiroche Gallery, London until June 7, 2019.

Concurrent exhibitions with works by Franz West are also on view at Tate Modern, London; David Zwirner, London and Hauser & Wirth, Zürich.